Misaligned sexual desire is the discrepancy or gap in the level of desire or interest in sex between sexual and/or romantic partners that results in distress or other relational challenges. This doesn’t only occur in long-term monogamous relationships; it can appear in any kind of sexual partnership including casual sex and open relationships. It’s also the most common reason individuals and couples alike seek out sex and relationship therapy.

The fact that misaligned desire is the predominant reason for seeking out sexual support makes tremendous sense when we recognise that desire discrepancies occur in almost all sexual relationships at some point. So, why is an experience that is as common as misaligned desire causing so much distress? And what do we need to know to better navigate it?

What is Sexual Desire?

Let’s start with what desire is not; desire is not a sex drive. Despite the popularity of this phrase, it’s inaccurate. When we use this term, we’re implying these are natural, primal needs and reinforcing the entitlement to sex that exits in society. Nobody needs sex to survive – they need connection, touch and pleasure – needs that sex can meet but sex is not the only way. Labelling desire a sex drive groups it with actual survival drives like hunger, thirst, sleep and safety.

Instead, sexual desire is wanting. It’s an experience that is informed by pleasure, that is interpersonal and relational. Desire has social meaning and closely tied to value systems, worth and desirability politics. It’s a motivational system, impacted by context. Context is a combination of the environment around you; what’s happening in your life, in the world and in your relationship as well as what’s happening internally; how you’re feeling or what you’re thinking.

Why Does Misaligned Desire Occur?

Sexual desire in any kind of relationship with another person(s) will likely never be completely aligned. This is because desire fluctuates and changes over your lifespan and your relationship. It’s also because people want different things at different times.

How often do you totally align in other areas of your life? Reflect on whether you typically agree on where to go for dinner, what movie to watch, or your sleep and wake cycles. It’s common and normal to have different preferences, including sex. A noticeable difference in desire is not automatically a sign of sexual incompatibility.

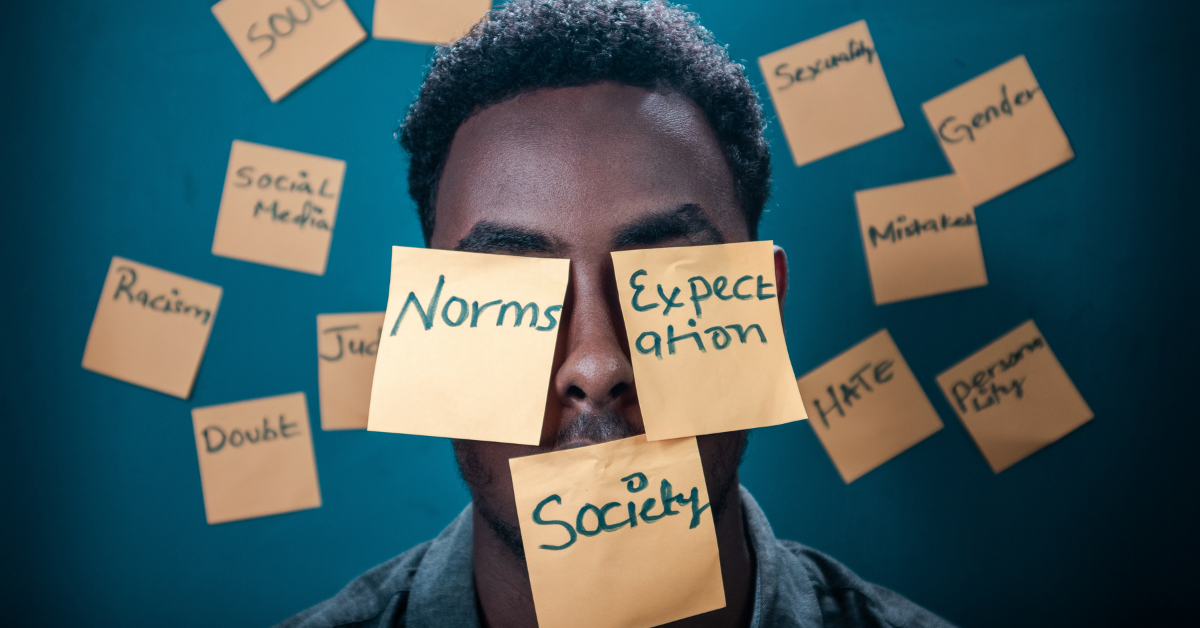

What tends to differ when it comes to sex is the social, cultural and interpersonal meaning we give it. The presence or absence of sex can seem highly significant when it becomes the primary way to give and receive love, be desired, feel worthy, bond, manage stress and experience pleasure. In turn, sexual frequency tends to become a measure of success or failure, where the strength of a relationship is valued based on a “normal amount” of sex defined by social norms.

Another common measure of sexual and relational success is the expectation for sex to happen spontaneously. However, if you’re waiting for sex or desire just to happen, you might find yourself waiting a long time, becoming frustrated or disappointed.

When you intentionally prioritise all else that matters in your life except sex, it’s possible you’re holding sex to a different standard and not making space for it. Think of desire like embers in a fire pit; something that requires intentional care so a fire can ignite, then the stoking and tending to of that fire when flames catch so they continue to burn. Instead of waiting for spontaneous desire to occur, we can intentionally grow responsive desire.

Responsive desire is desire which occurs in response to something pleasurable that is already happening. You need to slowly build up pleasure and interest without pressure or your breaks on. When you reflect on your accelerators list what would it be like to prioritise some of those things and give your mind and body time to respond?

The Breaks and Accelerators

What motivates and demotivates you to choose to have sex and feel desire is an integral piece of the puzzle. Pleasure is a significant motivator. You may be far more inclined to feel desire for things that feel good. Being emotionally overwhelmed, in conflict, obligated or unsafe tend to be massive demotivators.

Emily Nagoski, sexual educator and author popularised the idea of the accelerators and the breaks in her book Come As You Are, to describe this motivational sexual response system.

Your breaks, a sexual inhibitory system, are affected by contextual factors that signal to your brain that sex is not a good idea. For some people, being stressed, experiencing sex or touch that doesn’t feel pleasurable, pain, exhaustion, discrimination and oppression, exposure to racial trauma, anti-fatness or ableism, lack of privacy, heteronormativity and traditional gender roles can all signal your brain and body to turn off and shut down desire.

Your accelerator, a sexual excitatory system, responds to all the sexually relevant information in your environment that signals yes, sex! Experiencing touch that feels pleasurable, feeling desired, having strong sexual attraction, passing a delicious smelling person, feeling drawn towards someone, exploring using sex toys or games, seeing your partner in lingerie or wearing lingerie yourself, and for some being stressed and feeling drawn towards sex to bond, soothe or provide relief can signal your brain and body to turn on and increase your desire.

It’s also important to note that everyone has different levels of sensitivity of their breaks and accelerators. Someone may have a moderately sensitive break and accelerator but face strong forces hitting their breaks so their accelerators can’t gain any traction.

Try this: Make two lists; one that says accelerators/turn ons and another that says breaks/turn offs. Write down all the factors you can think of that might turn you on and turn you off. Share it with a partner if you have one or keep it close by and reflect on it often.

How to Navigate the Path of Misaligned Desire

Knowing that different levels of desire is an experience, not a pathology, knowing there is nothing biologically or psychologically wrong with someone with lower desire and believing that differences are not something to be fixed considerably reduces associated distress and increases ability to work through it, regardless of how big or small the difference is. To do that, three key things to consider is your awareness of why there’s a difference, knowing what you want or don’t want and finding other ways to connect.

1. Having awareness

How are you interpreting the experience of having differing levels of desire?

For instance, if your interpretation of misaligned desire is “we’re not right for each other”, “we’re sexually incompatible” or “I am broken” then it’s likely your breaks will be activated. A substantial amount of the distress of desire discrepancies arises out of feeling abnormal or being fearful this will be the demise of a relationship.

For an accurate interpretation, refer to your breaks and accelerators. How sensitive is your break and accelerator? What kind of week have you had? How much time have you been able to prioritise feeling close and connected? Have your accelerators had enough stimulation? Do you enjoy the kind of sex you’ve been having?

When you’re aware of what’s hitting your breaks, come up with a plan to deal with it. If the sex you’re having doesn’t feel pleasurable, what would feel better? If you’re dealing with lots of stress, explore coping strategies like physical activity, creative expression and affection to deal with the things you cannot change.

It’s also critical to be aware of and name any power dynamics. If your partner(s) is initiating sex and you notice they’ve just given you an ultimatum or recognise a consequence that makes it unsafe or difficult to say no, then that’s not practicing consent. If you’re in a safe and loving relationship, talk about how ultimatums take away choice and agency. This might sound like saying “I’m worried if I say no then you’ll be upset with me” or “how can I make it safer for you to tell me how you’re feeling or say no?”. We can’t remove power or privilege, but it’s our responsibility to try to mitigate it if we’re holding that power.

2. What do you want?

Ask yourself what might feel good? Think about what feels possible? What might you want? What doesn’t work for you? You may notice that part of you feels tired but another part wants to connect in a sensual and erotic way and need more time to respond sexually. You may not want to have routine sex, but feel like cuddling naked or using a sex toy to explore outercourse or mutual masturbation only if it doesn’t go further than that.

It’s possible to build responsive desire through intentionally prioritising all kinds of intimacy and doing things that feel pleasurable; spending time connecting with your accelerators might help you better decide what you do and don’t want.

We also need to be mindful of not violating our own consent. Notice when you say “I probably should just do it” or push yourself to have sex when you don’t want to. Nobody ever has to do something just because they’ve been invited or because society said it’s their job. Doing so will only hit your breaks, violate your consent, and turns sex into a stressful obligation – and that’s not ethical or pleasurable.

3. Finding connection

A no to sex doesn’t mean a no to connection. Sex is not a basic need. It is a great way to meet other needs, like the need for connection and pleasure, to be wanted and express and feel love. If you’re able to get curious and identify the underlying need that sex meets, communicate it early and explore your options to address it in other ways. This allows you to find the places where you overlap, shifting the pressure and entitlement away from a specific kind of partnered sex.

For example, if you want sex because it allows you to feel desired or have pleasure, how else can your partners help you have those things? How can you do that on your own? Through kind words or sexy texts? Through sensual rather than sexual touch?